EOLA-AMITY HILLS

GEOLOGY, SOILS & CLIMATE

The Story of the Soil of the Eola-Amity Hills

No grape variety is as reflective of site differences than Pinot Noir. Much of Pinot Noir’s magic lies in its ability to communicate a sense of the place where it was grown. While soil is not the only factor that gives Pinot noir its sense of place, there is no doubt that the fascinating diversity of Pinot noir wines grown in the Willamette Valley depends in no small part on the diverse origins of the soils in which our vineyards are planted.

Until about twelve million years ago, Western Oregon was on the floor of the Pacific Ocean. Prior to that, it was under the ocean for 35 million years, slowly accumulating layers of marine sediment, the bedrock of the oldest soils in the Willamette Valley.

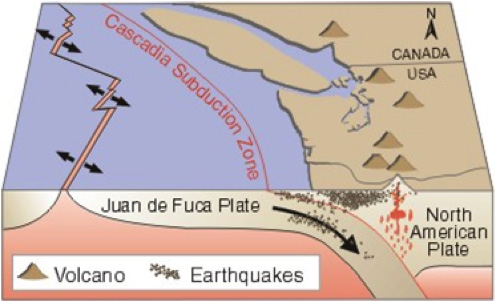

Starting about fifteen million years ago, the collision of the massive Juan de Fuca tectonic plate with the North American Plate drove this land up out of the water as the Juan de Fuca place slipped underneath the North American plate. Western Oregon rose out of the sea and kept rising, creating the Coast Range and the intensely volcanic Cascades Mountains further inland.

The Willamette Valley thus began as an ocean floor trapped between two emerging mountain ranges.

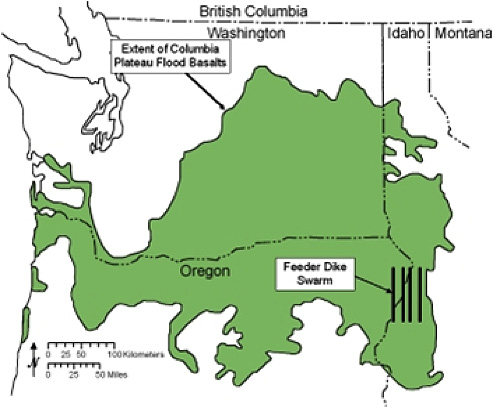

During this period of uprising, from about fifteen million to six million years ago, rivers of lava erupting from volcanoes on the east side of the Cascades flowed down the Columbia Gorge towards the sea, covering the layers of marine sediment on the floor of the emerging Willamette Valley with layers of basalt.

This map shows the area of the west coast, once submerged under the ocean until roughly 15 million years ago.

This map shows the area of the Oregon, Washington and Idaho that were covered in layers of Basalt.

This map shows the area of the Oregon, Washington and Idaho that were covered in layers of Basalt.

The Willamette Valley continued to buckle and tilt under pressure from the ongoing coastal collisions, forming the interior hill chains that are typically tilted layers of volcanic basalt and sedimentary sandstone, such as the Dundee Hills and Eola Hills.

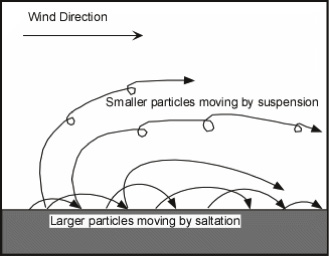

The next geologic activity to add to our soils was the creation of a layer of wind-blown silt called “loess”. This started as long ago as a million years and may have continued until about fifty thousand years ago. The silts that were blown came from the valley floor in the area, the remnants of the earlier basalts and sediments that had been pulverized by erosion for centuries. These winds left an incredibly fine-grained layer of dust on the northeast facing slopes in the Northern Willamette Valley.

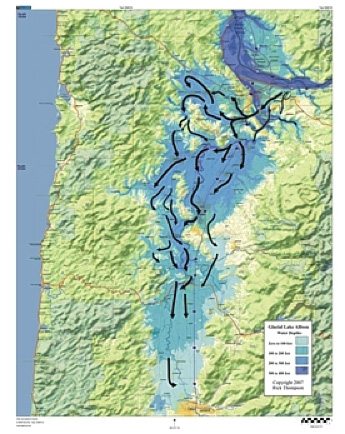

Much, much later, about eighteen thousand to fifteen thousand years ago, at the end of the last ice age, the melting of a glacial dam near the location of Missoula, Montana repeatedly flooded the Willamette Valley, creating a lake up to the 400-foot contour level, with only the tops of the two-tone hills sticking out. This left behind deep silts.

The formation of Loess is created by wind kicking up the fine dust particles in the air, where they eventually deposited back in a fine layer of silt.

As the water rushed toward the ocean, it came swirling into the Willamette Valley, forming Lake Allison, a body of water over 400 feet deep

Thus we have in the Willamette Valley a complex series of soils with interesting and diverse origins:

Marine Sediments

- Laid down on the floor of the Pacific Ocean

- Examples: Willakenzie, Bellpine, Chuhulpim, Hazelair, Melbourne, Dupee

Volcanic Basalts

- Originated as lava flows from eastern Oregon & Idaho

- Examples: Jory, Nekia, Saum

Ice Age Loess

- Silt blown up from the valley floor onto northeast-facing hillsides

- Example: Laurelwood

Missoula Flood deposits

- Brought down the Columbia Gorge via the recurring floods that happened each time the massive Lake Missoula’s glacial dam broke.

- Examples: Wapato, Woodburn, Willamette

- Much is said about how and why the Willamette Valley is the perfect place to grow Pinot noir. But, it must be said that not every acre in the Willamette Valley is suitable for growing great Pinot noir. Indeed, most of the Willamette Valley is filled with the deep, rich valley-floor soils brought to us all the way from Montana by the Missoula Floods at the end of the last ice age. These valley floor soils are paradise for a great diversity of crops, but they spell trouble for quality grape growing. Pinot noir at low elevations is subject to frost damage in the spring, and in such deep soils it becomes overly vigorous, and unable to ripen its fruit properly.